The authour after her release at a press conference in Bangkok.

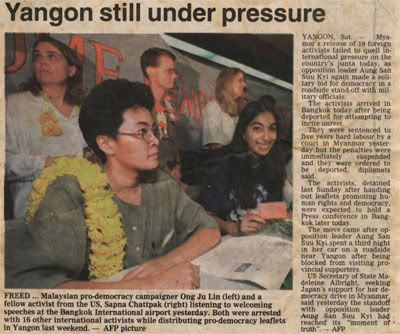

I WAS one of the 18 detained in Rangoon for six days. The six Americans have become international heroes. The other 12 - three Thais, three Indonesians, two Filipinas and one Australian are lesser (known) heroes, while the three Malaysians have been branded as "trouble-makers" in their own country.

In Burma, a different kind of media coverage were given on the incident. In The Mirror, a government propaganda news daily (as with all mass media in Burma), the editorial writes: “The people of Myanmar (Burma) can no longer bear the nefarious actions of the 18 alien instigators. The citizens of Myanmar (Burma) sees them, not as doves of peace, but crows of chaos. Because of that, they had helped the government arrest the 18.” – a lie as we were arrested by plainclothes policemen and not by the people.

Now with all the international attention on us, many may think that the action was very well planned, a commando team of democracy fighters sent forth on a mission, almost a conspiracy. Even the military was shaken. Eighteen people from six countries. Were they hand-picked?

Who was the mastermind? Who was the leader of the group?

In reality, nothing can be further from the truth. We come from all walks of life. A 19-year old American college kid. A 51-year old seasoned human rights activist. A journalist who knows more about writing than direct activism and facing 12 hours of interrogation.

We fumbled and drifted, not knowing what was coming next. Not knowing whether lying or telling the truth would get us out or further incriminate us. When our Malaysian Embassy officials came to see us, we thought we could seek some assurance from them. How wrong we were. All the first secretary could tell us was, ''Do you realise the consequences of your actions on bilateral ties?''

Sometimes we kept mum despite the shouts and threats from our interrogators. Your story is different from the rest. It is up to you, we were told. Sometimes we cooperated. We spilled information because we were scared. (In my mind, this is a rogue government with no care of what the world thinks.)

For three days, my two Malaysian colleagues and I were kept in the police headquarters before we were sent to a ''guesthouse'' to join the 15 others. We lived in an office, sharing it with a police officer of high rank, who came in at 9 am and left at 6 pm. Civil servant. He does his own things. People come in to see him, take orders, leave. On the second day he smiled at us. On the third day, he changed his longhi (sarong) into his military uniform in front of us. We became natural inhabitants of his office, like the ginkyoks (lizards) on the wall.

In the beginning we were defiant, cocky. We held on to our own. They too. Hard, indifferent looks. After all, they are in power, our captors. But as the days passed, they could neither feign power anymore than we could feign disdain. We lived together 24 hours a day in an office six by eight metres. They brought us food and cigarettes. They accompanied us to the toilet, our only excursions. Once in a while they came in to interrogate us. We fear interrogations. The uncertainties, the lies we have to keep up. The disbelief in their eyes. The continuous questions.

At night, they drape themselves on chairs and tables, while we sleep on mattresses under mosquito nets. I wrote my letters inside. On the third day, we got braver: will you get us bryiani rice from this shop at Sule Pagoda Road? We'll pay. To our delight, they did. The hard looks and indifference melted. Our smiles became genuine. Even our 'Thank you' (Je-zu-tin-bateh).

They smiled at seeing us enjoy our meal, they could not hide. Our captors, they become people in my eyes. They fear us, and hate us, but came to like us. Me too, though to admit it is as if to imply that the junta, with their human rights abuses and atrocities, are okay.

We have a constant attendant, a spy you could say, who watched our every move, and was present at every interrogation, who would not tell us what was going on, or would only tell us lies. ''How long will we be kept here?'' ''Very long.'' ''How long? Forever?'' ''Yes.''

Once I said, ''Don't ask him anything. He only tells lies.'' I notice a sting of hurt in his eyes. He doesn't hide very well. Neither do the others. Neither do I. I came home with a knot in my chest that wouldn't go away. We came home jubilant and triumphant. Heroes. But I did not feel jubilant and triumphant. I was ashamed, not for what I did, (leafletting). But because I really didn't want to see my captors as people, so I can come home and condemn the junta with authoritative vigour. So I can mock their ignorance and stupidity. My captors who are part of the junta, who work a 9-to-5 job, and go home to their families and TV sets.

A small piece in a monstrous structure; which is responsible for more than 10,000 of its people fighting for democracy in exile; which is responsible for arbitrary arrests, tortures and deaths of elected representatives and activists;which is responsible for the butchery and rapes of ethnic minorities; who is responsible for the 120,000 refugees languishing on the borders of Thailand. But I come home and I still think of them.

Is he responsible? Richard, our interrogator with a big pot belly? Who shouted at me for not co-operating. He, whom we taught how to play cards; who patiently listened and translatedinto Burmese for his other colleagues; who passed his cards to his friend while he ran to answer a phone call. He who promised to teach us a Burmese card game before we left.

Or how about the woman attendant who insisted on standing and watching me bathe? When I look into her eyes, she is as naked to me as I am to her.

Or is it the guard we affectionately call the flower boy, who would go outdoors to pick flowers for our hair? Which do you want?'' ''The yellow ones.'' We made our choice peering out from the windows of our prison.

Or was Khin Maung, the judge, responsible? His dedication to his job was admirable. Eight hours of sitting in his big, hard chair wearing a yellow scarf with a wing-like-thing on the right side of his head. Listening patiently to statements from police officers and witnesses.

His sentencing, he delivered with utmost seriousness, five years in Insein Prison, only to be negated moments later by the auspiciousness of the Foreign Affairs Ministry. We were to be pardoned and deported. But he played his role well.And so we came back as heroes. Freedom fighters. We joked about the ridiculousness of the whole experience. The trial, the interrogation, the investigations of us. We mocked them and their antics. We condemned the junta. We talked about human rights and democracy, as if our experience has anything to do with the violent realities of Burma.

In our roles of heroes, we are as much actors in a play -- a shadow play -- as Richard, the judge, or the 'Flower Boy'. We play into what is expected of us by following a director's orders. In our case the director is the world, the media. Who then is the master puppeteer in Burma? Again I ask, who is responsible while people are tortured and killed? Those who direct, those who participate, those who stand and watch, or those who try to lead a 9-to-5 job, concentrating hard on their work so they won't hear cries of pain, loss and death.

If those in the last group, the 9-to-5 people in Burma are to be condemned, so should anyone around the world who has ignored the suffering in Burma. Or in East Timor. Or Turkey. Or Mexico.

As there are different degrees of degree of blame and responsibility, then there are also degrees of heroism. On one extreme, the Americans see us as gallant heroes, taking on a military regime. I feel I do not fit there. Neither do I deserve the Malaysian government's condemnation of our actions and labelling us as trouble-makers and law-breakers. We went there to do a good thing for a forgotten people, and that we took risks to our best.

During those six days, I discovered humanity behind the villain's mask which they cannot hide despite the fact that in Burma, the actors carry guns. Total evil is a clear target, a defined red bull's-eye in the centre of a white circle. In Burma, I found that the paint was mixed to a solid pink, bad inseparable from good. Humans. Like me. I will continue to do what I do, to fight for the rights of the oppressed under the military rule of Burma. I will write articles, compile updates, research, lobby, not so much of conviction, but perhaps for a lack of wisdom to do something different.

(I wish to thank Amy deKanter who has helped me throughout the process of writing this article. Thank you for giving me a safe space to allow me to remove my mask.)

Published in The Nation August 21,1998