by ONG JU LIN

XANANA Gusmao and Jose Ramos Horta's visit to Malaysia in February signified a new era in Malaysia's relationship with East Timor. Just six months before that, Malaysia had accused the West of taking advantage of Indonesia following the fall of Suharto and orchestrating East Timor's independence. Today, the Malaysian Government has pledged to help East Timor rebuild their country.

Foreign Minister Datuk Seri Syed Hamid Albar, in welcoming the East Timorese leaders, said, "It is important for us to look at East Timor as an independent country and we will continuously build up the relationship based on this.''

This rapid turnaround in Malaysia's response to East Timor before and after its independence calls for more scrutiny of our foreign policy, observes Dr Sumit Mandal, lecturer at Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (Ikmas) of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

"The implications of recent events concerning East Timor beg us to look into the meaning of the non-interference principle which Malaysia held to during the 24 years of Indonesian domination,'' he says.

As an Asean member country, Malaysia abides by that principle in the internal affairs of a member country. This is the founding principle of Asean, the basis of which is to avoid political and military conflicts and to foster regional economic development.

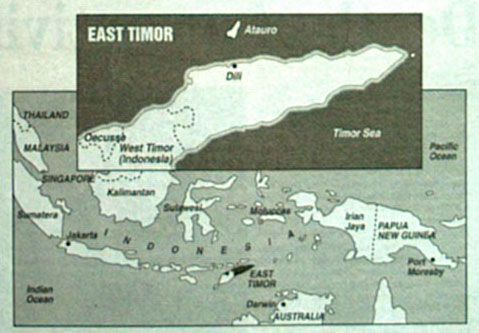

Right from the start, when Indonesia invaded East Timor, Asean had dismissed East Timor's long struggle for independence as an internal affair of Indonesia. When Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975, Malaysia, with all other Asean member countries (except Singapore), in an act of Asean solidarity, voted for Indonesia when the United Nations General Assembly condemned the invasion and called for Indonesia to withdraw. Singapore fell in line in 1977.

The invasion was not only sanctioned by Asean countries but by Western superpowers too. American complicity in Indonesia's invasion and subsequent repression of East Timor has been amply documented. According to American author and political analyst Noam Chomsky, US backing of Indonesia came as a result of fear that East Timor would become a "South-East Asian Cuba''.

The fear of communism taking root in an economically and politically important region drove the United States into providing the means of invasion. In fact, the invasion was in full force after the visit of American President Gerald Ford to Jakarta in 1975 during which his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, gave his blessings to Suharto, asking the invasion to be quick and efficient.

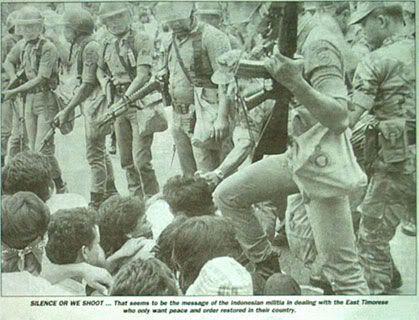

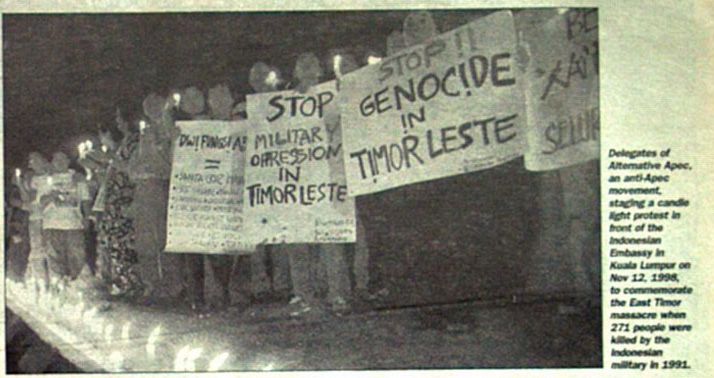

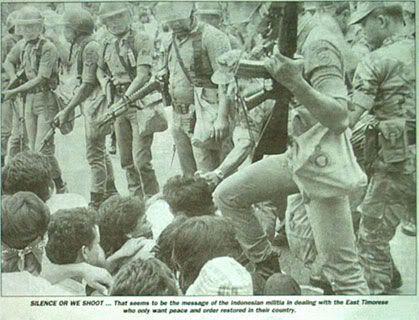

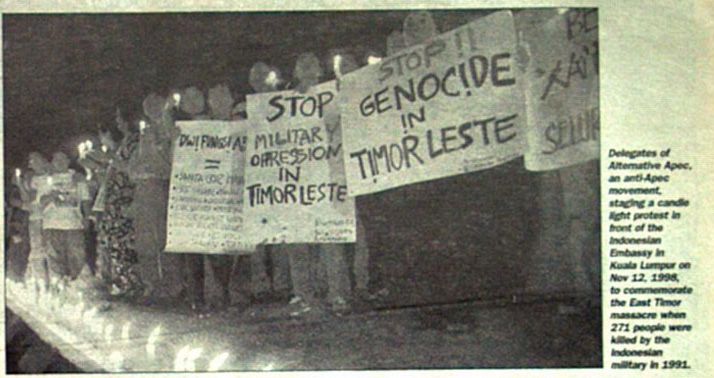

In another show of support for Indonesia, Asean member countries again abided by the policy of non-interference in the Nov 12, 1991, Dili Cemetery Massacre. Eye-witness accounts and a video recording by British filmmaker Max Stahl showed that the Indonesian military had opened fire at unarmed demonstrators, killing 271 people, including 20-year-old Malaysian student Kamal Bamadhaj who was shot outside the cemetery.

Kamal's death went largely unreported in the Malaysian media. But the Dili killings brought international attention to East Timor's struggle and even seeped through to the citizens of Asean member countries. However, efforts to help the Timorese were mostly confined to NGOs.

One such effort was the Asia-Pacific Coalition on East Timor (Apcet) conference. It was first held in Manila in 1994 to show South-South solidarity with the Timorese.

The second Apcet was held in Kuala Lumpur in 1996 despite the expressed disapproval of the Malaysian Government. The conference was disrupted by members of the ruling coalition Barisan Nasional Youth Wing who blamed the organisers for spoiling the good relations between Indonesia and Malaysia. Police arrested 59 participants, including foreign journalists, and most of the organisers, who were locked up for up to a week.

Despite all this, the Malaysian Government's conscience appears to be clear. Expressing the Malaysia's government's sentiment, political scientist Dr Lukman Thaib of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia says that East Timorese leaders were given the opportunity to understand Malaysia's position during their February visit.

"It was not morally proper to support the East Timorese struggle at the expense of the non-interference policy until the outcome of the 1999 referendum which showed the real intention of the people,'' he argues.

Furthermore, it is said that Malaysia's policy on East Timor has never changed.

"We have always supported Indonesia when East Timor was its territory and now, when it has ceased to be. We have always been consistent with our policy,'' says Kamal Ismaun, under secretary for South-East Asia and South Pacific Division at Wisma Putra.

The rationalisation now is that since Indonesia has acceded to East Timor's wish to be an independent nation through the August 1999 referendum, Malaysia will accord East Timor the respect of an independent nation and recognise it as such.

Former Asean secretary-general Tan Sri Datuk Ajit Singh says that in East Timor's case, we should put the past behind, look ahead and try to help the fledgling nation get back on its feet.

"East Timor has gone through some very tragic events and it is time to rebuild it."

Indeed, Malaysia's response to East Timor since the referendum has been largely positive. It has promised technical aid as well as diplomatic and administrative assistance in reconstructing East Timor.

However, for many observers, such nationalistic rasionalisations are far from adequate. Not only do the wrong-doers of the past have to be brought to justice, but lessons have to be learnt from the East Timor experience.

Suaram spokesperson Elisabeth Wong says that it is time Asean takes a critical look at the policy of non-interference because it deflects questions of human rights violations. "Asean must take a stronger stand on issues of human rights abuses. It must respond to calls for help by people in troubled areas within Asean.''

Parti Rakyat President Dr Syed Husin Ali calls for greater flexibility in the policy of non-interference. "The policy of non-interference is good in that it prevents conflict at government level, but it should not be taken to such an extreme at the cost of human lives. Asean should be flexible and tolerant of mutual criticisms.

"Raising issues of greater democratisation and giving its views to overcome problems and conflicts in another member country should not be seen as interference in the internal affairs of another country,'' he says.

However, Ajit Singh contends that Asean should still stand firm on its principle of non-interference. He believes that it is because of the principle that Asean has been able to avoid major conflicts among members and resolve problems peacefully for the last 32 years.

"Lately, it has come under close scrutiny as a result of what happened in East Timor, Kosovo and other parts of Africa. But in my opinion, the principle should still stand,'' he says.

Ajit Singh, however, concedes that if there are violations of human rights in a certain member country, it is within one's right to comment and bring to the attention of the international community and try to help. "But it must not be done by commenting negatively,'' he says.

Dr Khoo Boo Teik of Universiti Sains Malaysia agrees that it is very difficult for neighbouring countries to continually interfere in the affairs of each member country. Alternatively, he says, Asean could allow citizen groups, NGOs, and peoples' initiatives to carry out networking and create solidarity among member countries in voicing out concerns of human right abuses and similar issues.

Says Khoo: "The question is, would Asean make a commitment to allow for more democratic space and solidarity among its people?''

While Asean is still a long way from having an actual clause on human rights, leaders from the Philippines and Thailand have spoken out for greater democratic space and awareness of human rights issues among member countries.

Indonesia has since adopted a more democratic approach and has a greater awareness on human rights with Abdurrahman Wahid's government which was elected in a free and fair election. And deposed president Suharto is to be tried by the new government for alleged corruption during his 32 years of power.

The challenge now is for Asean to come to terms with lessons learnt from East Timor and adopt a more effective mechanism to address similar problems in future.

Published in The Star Malaysia May 9, 2000 (www.thestar.com.my)

Tuesday, May 09, 2000

Monday, May 08, 2000

Death of an Activist

by Ong Ju Lin

“He was totally, totally innocent and his death was an abosolutely unforgivable murder.”

Jose Ramos Horta, independence deputy leader of East Timor

Unlike most Malaysians who recently became familiar with East Timor’s long and tragic struggle for independence, one young man, Kamal Bhamadhaj, worked tirelessly from 1989 until his death in 1991to raise international support and awareness for the East Timorese. He was killed by the Indonesian military on Nov 12, 1991, because he had become too visible and activist. These series of articles trace the life of this remarkable young man whose life and death became an award-winning documentary and explain why hardly anyone in this country has heard of him.

NINETEEN-ninety-one was an eventful year. Problems in Bosnia were brewing. The Israelis were settling on the Gaza strip and the West Bank in greater concentration, displacing the Palestinians from their land. Apartheid was being dismantled in South Africa.

In all three cases, Malaysia responded with strong statements in support of the oppressed and displaced. But few Malaysians were aware of the extent of fear, violence and starvation wrought on a people since 1975 on an island much closer to home. That was the year Indonesia invaded East Timor. In the years that followed, the Timorese were subjected to rape, torture, arbitrary arrests (leading to many disappearing without a trace) and widespread starvation.

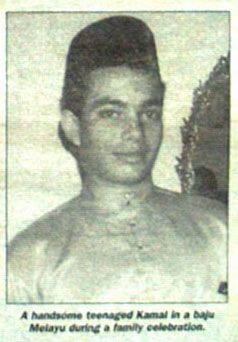

In 1991, too, Indonesian soldiers fired bullets at a crowd of 2,000 unarmed Timorese protestors demonstrating for an end to military brutalities and demanding for independence. In what has become known as the Dili Cemetery Massacre, 271 people were killed. One of them was a Malaysian. His name was Kamal Ahmed Bamadhaj.

Shortly after his death, an Utusan Malaysia report entitled Kamal Ahmed Bamadhaj, "He Blew the Fire of Love of Humanity" and printed an excerpt from his diary. But what was very strange was that the report made no mention of where he was killed, merely saying vaguely that it was "in a territory in a region in the world."

Such was the secrecy that enveloped Kamal's death and the slaughter of 270 East Timorese on Nov 12, 1991, in vast contrast to the ample coverage given by the local media to affairs of nations as far as Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

In recounting the events after the Dili Massacre, Kamal's sister, Nadiah, 31, says: ``Nothing could be a clearer (indication) of Asean complicity than the local media's treatment of the killings."

For fear of angering Indonesia, the media downplayed Kamal's death and the massacre. As a member of Asean, Malaysia abides by the principle of non-interference that means a member country does not interfere in the domestic affairs of another member country. Indonesia's invasion of East Timor in 1975 was considered the domestic affair of Indonesia.

Reports of torture and other atrocities committed against the Timorese were muted in Asean's media. In the name of non-interference, Asean leaders stood in solidarity with the Suharto regime as far as East Timor was concerned even when a Malaysian became a casualty of the Indonesian military.

Kamal was barely 21 when he died. His death was, as East Timorese leader Jose Ramos Horta describes it, "(an) absolutely unforgivable murder."

Kamal, who had been living in Sydney, Australia, in 1991 was planning to go to Dili to act as an interpreter for an Australian aid worker, Bob Muntz, when word got around that Ramos Horta was looking for someone to act as a courier.

Ramos Horta wanted to send information to the East Timorese resistance concerning the itinerary of the visit of the United Nations/Portugal Delegation to East Timor.

Kamal had been involved in the resistance movement two years before and wanted to help by bringing world attention to the oppression and human rights abuses in East Timor. He arrived in Dili on Oct 24, 1991, several days ahead of the delegation's expected arrival. But on Nov 3, word went out that the visit had been cancelled. If they had come, the Portuguese would have been the first foreign delegation allowed into the troubled territory since Indonesia's annexation 16 years before.

"Hearts sank. People cannot believe it. In the past month, Timorese have been taking extraordinary risks organising themselves in anticipation of the delegation, wrote Kamal in his diary. "They claim that any risk they took was worth it because the visit will offer them so much hope. But now the visit is off and the Timorese are once again in the all too familiar position of being defenceless from arbitrary arrest, maltreatment or even death."

These were to be Kamal's last words in his diary. In his final conversation with Bibi Langker, his Australian girlfriend, Kamal had sounded different that morning. "He was totally relaxed and being silly. It was unlike his earlier conversations where he sounded totally freaked out and tensed," says Langker in the New Zealand-made documentary, Punitive Damage, which recounts Kamal's death and his mother's four-year battle to bring his killer to justice.

On the morning of Nov 12, 1991, Kamal set off to join demonstrators in commemorating the killing of 16-year-old Sebastiao Gomes who was shot on Oct 28 by Indonesian soldiers who attacked a church, where Gomes and several youths were staying. The commemoration mass swelled to several thousand people and, as they marched in protest from the church to the Santa Cruz cemetery where Gomes was buried, they unfurled banners calling for independence and a stop to the atrocities committed against the Timorese people.

Upon reaching the cemetery, according to the testimony of eye-witness Allan Nairn, an American journalist, truckloads of armed soldiers descended from their vehicles in an orderly fashion, marched up into the crowd and, without warning, started shooting. The terrifying scene of people falling on top of each other trying to escape through the main exit of the cemetery was vividly caught by British filmmaker Max Stahl in his documentary, In Cold Blood.

The high walls of the cemetery prevented many from escaping. In one scene, the camera captured a man dying from gunshot wounds, his head cradled by his friend. Kamal was shot moments later, outside the cemetery.

"Kamal did not die for nothing. It's intriguing that years after his death, he is still remembered in different ways," says his father, Ahmed. His death spurred those who knew him to work towards East Timor's peace in their own ways.

To deal with her grief, his sister Nadiah, for instance, took to learning about Kamal's activism in South-East Asia and human rights issues. And what she learnt, she shared with others. Nadiah went on to write on East Timor and publish Kamal's diaries and letters in the book, Aksi Write(Rhino Press), in 1997. She is currently working on the second edition to be published some time in June this year.

Recounting the events after Kamal's death, Nadiah says: "I did not know that world leaders were turning a blind eye to such atrocities in East Timor. I guess that knowledge is the most beneficial thing that came out of Kamal's death for me. But it is too terrible a price to pay for that knowledge."

In 1994, Kamal's mother, Helen Todd, aided by the US Center for Constitutional Rights, sued the Indonesian army's regional commander, General Sintong Panjaitan, holding him responsible for her son's death and the deaths of the 270 others.

After the massacre, in response to international outrage, the Indonesian Government sent Panjaitan and another commander to Harvard University in Boston to study English as "punishment''. Using a little-known 200-year-old US law which allowed human rights violators to be tried wherever they were found, Todd sued for compensatory and punitive damages.

Panjaitan, upon receiving his summons, immediately fled back to Indonesia. The suit, however, continued and the US court eventually awarded Todd and Kamal's estate a total of US$22mil (RM83.6mil). Panjaitan refused to acknowledge the court's jurisdiction, calling the suit a "joke''.

Todd gave countless interviews to the international media and played a crucial role in the documentary, Punitive Damage. Her tireless work contributed to a greater awareness of what actually happened in East Timor during the 24 years of Indonesian occupation and the events on that fateful day in November 1991.

But her collaboration with the filmmakers was her last "public appearance'', as she put it when contacted for this article. "It was very painful doing the film. I don't want to play the grieving mother anymore,'' she said, in turning down our request for an interview.

Kamal's friends in the students' organisation, Network of Overseas Student Collectives (Nosca) in Australia, pledged to work in their own capacities until East Timor was independent. Elisabeth Wong, a Malaysian who is now coordinating the collection of clothes and food to be sent to East Timor says: "Kamal's death changed us. We were no longer a bunch of idealists. We were suddenly faced with the reality that our friend, whom we considered a family member, died in the cause of his activism. It made our struggles more real and we became more committed to the cause."

In 1996, Wong and former Nosca members, with the support of other organisations, organised the Apcet II (Asia-Pacific Coalition on East Timor) conference to raise awareness on East Timor issues and to find a peaceful solution to the struggle.The conference, however, was disrupted by UMNO Youth (the ruling party's youth wing) members and the organisers detained. The incident made it crystal clear that the Malaysian Government was determined to silence any attempts by citizens' groups to bring up the issue of East Timor or of Kamal's death.

The fall of Suharto in 1998, which paved the way for East Timor's independence, and the ensuing excitement of rebuilding have overshadowed old horrors. But the memories of Kamal remain. He is remembered in quiet ways by people who may or may not have known him when he was alive.

"Months after he was buried, there were still notes, flowers, letters, on his grave,'' says Ahmed who visits his son's grave in Bukit Kiara, Kuala Lumpur, regularly to offer prayers. "I was told by the gatekeeper that even now someone would come, sit for an hour, and then another couple would come, sit and weep together. People remember him.

"Retracing Kamal's travels in Indonesia a few years after he was killed, Wong recalls that villagers whom Kamal met along the way still remembered him. "When I told them that Kamal had been killed, they wept openly."

"Kamal did what he did, not because of religious affiliations or regional politics or for any kind of fame. Observes Ahmed: "It was something very simple, very basic: He loved people, and their suffering tormented him. He did what he could for a forgotten people."

To date, the Malaysian Government has yet to acknowledge, much less put up any protest in recognition of, that one of its citizens was wrongfully killed by Indonesia under the Suharto regime.

The Center for Constitutional Rights, however, is pursuing the case and Todd has said any money she receives from the damages would be donated to families of the victims of the Dili Massacre.

Sintong Panjaitan, who joined the Indonesian public service, rose to become an adviser to President B.J. Habibie. Attempts to locate him came to naught. Thus far, he has not been brought to answer for his crimes.

Published in The Star Malaysia on May 8, 2000. (www.thestar.com.my)

“He was totally, totally innocent and his death was an abosolutely unforgivable murder.”

Jose Ramos Horta, independence deputy leader of East Timor

Unlike most Malaysians who recently became familiar with East Timor’s long and tragic struggle for independence, one young man, Kamal Bhamadhaj, worked tirelessly from 1989 until his death in 1991to raise international support and awareness for the East Timorese. He was killed by the Indonesian military on Nov 12, 1991, because he had become too visible and activist. These series of articles trace the life of this remarkable young man whose life and death became an award-winning documentary and explain why hardly anyone in this country has heard of him.

NINETEEN-ninety-one was an eventful year. Problems in Bosnia were brewing. The Israelis were settling on the Gaza strip and the West Bank in greater concentration, displacing the Palestinians from their land. Apartheid was being dismantled in South Africa.

In all three cases, Malaysia responded with strong statements in support of the oppressed and displaced. But few Malaysians were aware of the extent of fear, violence and starvation wrought on a people since 1975 on an island much closer to home. That was the year Indonesia invaded East Timor. In the years that followed, the Timorese were subjected to rape, torture, arbitrary arrests (leading to many disappearing without a trace) and widespread starvation.

In 1991, too, Indonesian soldiers fired bullets at a crowd of 2,000 unarmed Timorese protestors demonstrating for an end to military brutalities and demanding for independence. In what has become known as the Dili Cemetery Massacre, 271 people were killed. One of them was a Malaysian. His name was Kamal Ahmed Bamadhaj.

Shortly after his death, an Utusan Malaysia report entitled Kamal Ahmed Bamadhaj, "He Blew the Fire of Love of Humanity" and printed an excerpt from his diary. But what was very strange was that the report made no mention of where he was killed, merely saying vaguely that it was "in a territory in a region in the world."

Such was the secrecy that enveloped Kamal's death and the slaughter of 270 East Timorese on Nov 12, 1991, in vast contrast to the ample coverage given by the local media to affairs of nations as far as Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

In recounting the events after the Dili Massacre, Kamal's sister, Nadiah, 31, says: ``Nothing could be a clearer (indication) of Asean complicity than the local media's treatment of the killings."

For fear of angering Indonesia, the media downplayed Kamal's death and the massacre. As a member of Asean, Malaysia abides by the principle of non-interference that means a member country does not interfere in the domestic affairs of another member country. Indonesia's invasion of East Timor in 1975 was considered the domestic affair of Indonesia.

Reports of torture and other atrocities committed against the Timorese were muted in Asean's media. In the name of non-interference, Asean leaders stood in solidarity with the Suharto regime as far as East Timor was concerned even when a Malaysian became a casualty of the Indonesian military.

Kamal was barely 21 when he died. His death was, as East Timorese leader Jose Ramos Horta describes it, "(an) absolutely unforgivable murder."

Kamal, who had been living in Sydney, Australia, in 1991 was planning to go to Dili to act as an interpreter for an Australian aid worker, Bob Muntz, when word got around that Ramos Horta was looking for someone to act as a courier.

Ramos Horta wanted to send information to the East Timorese resistance concerning the itinerary of the visit of the United Nations/Portugal Delegation to East Timor.

Kamal had been involved in the resistance movement two years before and wanted to help by bringing world attention to the oppression and human rights abuses in East Timor. He arrived in Dili on Oct 24, 1991, several days ahead of the delegation's expected arrival. But on Nov 3, word went out that the visit had been cancelled. If they had come, the Portuguese would have been the first foreign delegation allowed into the troubled territory since Indonesia's annexation 16 years before.

"Hearts sank. People cannot believe it. In the past month, Timorese have been taking extraordinary risks organising themselves in anticipation of the delegation, wrote Kamal in his diary. "They claim that any risk they took was worth it because the visit will offer them so much hope. But now the visit is off and the Timorese are once again in the all too familiar position of being defenceless from arbitrary arrest, maltreatment or even death."

These were to be Kamal's last words in his diary. In his final conversation with Bibi Langker, his Australian girlfriend, Kamal had sounded different that morning. "He was totally relaxed and being silly. It was unlike his earlier conversations where he sounded totally freaked out and tensed," says Langker in the New Zealand-made documentary, Punitive Damage, which recounts Kamal's death and his mother's four-year battle to bring his killer to justice.

On the morning of Nov 12, 1991, Kamal set off to join demonstrators in commemorating the killing of 16-year-old Sebastiao Gomes who was shot on Oct 28 by Indonesian soldiers who attacked a church, where Gomes and several youths were staying. The commemoration mass swelled to several thousand people and, as they marched in protest from the church to the Santa Cruz cemetery where Gomes was buried, they unfurled banners calling for independence and a stop to the atrocities committed against the Timorese people.

Upon reaching the cemetery, according to the testimony of eye-witness Allan Nairn, an American journalist, truckloads of armed soldiers descended from their vehicles in an orderly fashion, marched up into the crowd and, without warning, started shooting. The terrifying scene of people falling on top of each other trying to escape through the main exit of the cemetery was vividly caught by British filmmaker Max Stahl in his documentary, In Cold Blood.

The high walls of the cemetery prevented many from escaping. In one scene, the camera captured a man dying from gunshot wounds, his head cradled by his friend. Kamal was shot moments later, outside the cemetery.

"Kamal did not die for nothing. It's intriguing that years after his death, he is still remembered in different ways," says his father, Ahmed. His death spurred those who knew him to work towards East Timor's peace in their own ways.

To deal with her grief, his sister Nadiah, for instance, took to learning about Kamal's activism in South-East Asia and human rights issues. And what she learnt, she shared with others. Nadiah went on to write on East Timor and publish Kamal's diaries and letters in the book, Aksi Write(Rhino Press), in 1997. She is currently working on the second edition to be published some time in June this year.

Recounting the events after Kamal's death, Nadiah says: "I did not know that world leaders were turning a blind eye to such atrocities in East Timor. I guess that knowledge is the most beneficial thing that came out of Kamal's death for me. But it is too terrible a price to pay for that knowledge."

In 1994, Kamal's mother, Helen Todd, aided by the US Center for Constitutional Rights, sued the Indonesian army's regional commander, General Sintong Panjaitan, holding him responsible for her son's death and the deaths of the 270 others.

After the massacre, in response to international outrage, the Indonesian Government sent Panjaitan and another commander to Harvard University in Boston to study English as "punishment''. Using a little-known 200-year-old US law which allowed human rights violators to be tried wherever they were found, Todd sued for compensatory and punitive damages.

Panjaitan, upon receiving his summons, immediately fled back to Indonesia. The suit, however, continued and the US court eventually awarded Todd and Kamal's estate a total of US$22mil (RM83.6mil). Panjaitan refused to acknowledge the court's jurisdiction, calling the suit a "joke''.

Todd gave countless interviews to the international media and played a crucial role in the documentary, Punitive Damage. Her tireless work contributed to a greater awareness of what actually happened in East Timor during the 24 years of Indonesian occupation and the events on that fateful day in November 1991.

But her collaboration with the filmmakers was her last "public appearance'', as she put it when contacted for this article. "It was very painful doing the film. I don't want to play the grieving mother anymore,'' she said, in turning down our request for an interview.

Kamal's friends in the students' organisation, Network of Overseas Student Collectives (Nosca) in Australia, pledged to work in their own capacities until East Timor was independent. Elisabeth Wong, a Malaysian who is now coordinating the collection of clothes and food to be sent to East Timor says: "Kamal's death changed us. We were no longer a bunch of idealists. We were suddenly faced with the reality that our friend, whom we considered a family member, died in the cause of his activism. It made our struggles more real and we became more committed to the cause."

In 1996, Wong and former Nosca members, with the support of other organisations, organised the Apcet II (Asia-Pacific Coalition on East Timor) conference to raise awareness on East Timor issues and to find a peaceful solution to the struggle.The conference, however, was disrupted by UMNO Youth (the ruling party's youth wing) members and the organisers detained. The incident made it crystal clear that the Malaysian Government was determined to silence any attempts by citizens' groups to bring up the issue of East Timor or of Kamal's death.

The fall of Suharto in 1998, which paved the way for East Timor's independence, and the ensuing excitement of rebuilding have overshadowed old horrors. But the memories of Kamal remain. He is remembered in quiet ways by people who may or may not have known him when he was alive.

"Months after he was buried, there were still notes, flowers, letters, on his grave,'' says Ahmed who visits his son's grave in Bukit Kiara, Kuala Lumpur, regularly to offer prayers. "I was told by the gatekeeper that even now someone would come, sit for an hour, and then another couple would come, sit and weep together. People remember him.

"Retracing Kamal's travels in Indonesia a few years after he was killed, Wong recalls that villagers whom Kamal met along the way still remembered him. "When I told them that Kamal had been killed, they wept openly."

"Kamal did what he did, not because of religious affiliations or regional politics or for any kind of fame. Observes Ahmed: "It was something very simple, very basic: He loved people, and their suffering tormented him. He did what he could for a forgotten people."

To date, the Malaysian Government has yet to acknowledge, much less put up any protest in recognition of, that one of its citizens was wrongfully killed by Indonesia under the Suharto regime.

The Center for Constitutional Rights, however, is pursuing the case and Todd has said any money she receives from the damages would be donated to families of the victims of the Dili Massacre.

Sintong Panjaitan, who joined the Indonesian public service, rose to become an adviser to President B.J. Habibie. Attempts to locate him came to naught. Thus far, he has not been brought to answer for his crimes.

Published in The Star Malaysia on May 8, 2000. (www.thestar.com.my)

Friday, May 05, 2000

Kamal's Final Moments

by June HL Wong and Ong Ju Lin

WHEN the Indonesian soldiers started pumping bullets into the East Timorese protesters at the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili on Nov 12, 1991, Malaysian activist Kamal Bamadhaj was near the front of the crowd.

He somehow survived the murderous hail, apparently sustaining only an arm injury, acording to a medical report his mother, Helen Todd received later. Eye-witnesses saw him walking away alone from the scene of carnage, barefoot.

In the documentary, Punitive Damage, Jose Verdial, a Timorese who took part in the demonstration, said he saw Kamal walking towards him, outside the cemetery, when a military truck that was following him pulled up next to him. An argument ensued, apparently over the camera Kamal was holding.

Seconds later, Kamal was shot in his chest by a military intelligence officer who had come out of the truck. He was left lying on the roadside. Kamal did not die immediately and had managed to flag down a passing Red Cross ambulance.

"When he was helped by the Red Cross, he was still talking,'' recounted Verdial. "Every time he spoke, blood gushed out from his wound.''

Further investigations by Todd revealed that Kamal died of blood loss as a result of delays in getting him to the hospital. The Red Cross ambulance was stopped twice by military and police road blocks.

At the second block, the police forced the ambulance driver into a police station compound and demanded he dump Kamal there. The courageous driver refused. He was finally allowed to send Kamal, who was bleeding profusely, to hospital. By that time, it was too late. He died 20 minutes later.

In Punitive Damage, American journalist Allan Nairn, who knew Kamal, recalled how tense and explosive the situation was in Dili, following the killing of a Timorese youth, Sebastiao Gomes, in a church by Indonesian soldiers on Oct 28 and the cancellation of the United Nations sponsored visit by a delegation of Portuguese parliamentarians on Nov 3.

Nairn said that when the soldiers attacked the Motael Church, it stunned the people because their "final sanctuary had been violated."

When word got out that the delegation's visit had been called off, the Timorese were in total despair. They had pinned tremendous hopes on the visit. At last, after 16 years of brutal oppression and isolation, the world would finally learn of their plight.

Many of the Timorese, defying the authorities' warnings of reprisal if they spoke to the Portuguese, had been preparing to gain the delegation's attention with banners and petitions. With the beacon of hope extinguished, they feared they would be singled out and killed.

Kamal, who knew many of the young Timorese, felt their fear and despair. He called his Australian girlfriend, Bibi Langker, in Sydney begging her to do something.

"He was desperate for the Portuguese to come. He asked me to go to the embassy to get them to come. He was really, really upset," she said in Punitive Damage.

When the Timorese decided to organise a memorial march for Gomes, Kamal begged the Western journalists (who were staying in the same hotel with him in Dili) to be present in the hope it would prevent violence by the Indonesian troops.

"Kamal himself was actually quite nervous about going. Then he decided to go and he got himself a camera," said Nairn.

Helen Todd marvels that "this boy who could never get up in the morning" set his alarm clock for 5.30am and woke everyone else.

The march started from the church near the beach and moved on to the cemetery. As they went along, the protestors pulled out banners calling for freedom.

As they gathered in the cemetery, Indonesian soldiers arrived and started shooting. "I couldn't believe it. At first I thought they were firing blanks. Then I saw people crumpling. They were being shot in the back as they tried to escape," recounted Nairn.

He said when the shooting stopped, the soldiers moved in and beat and stabbed the hapless Timorese still trapped in the cemetery.

Nairn, who sustained a cracked skull, said he survived because he shouted to the soldiers that he was American. He guessed, apparently correctly, that the Indonesians wouldn't kill a citizen of a nation which was supplying them with the guns and bullets.

A total of 271 people died that day, including Kamal, Malaysia's only casualty in the East Timorese cause.

Todd was prevented by the Indonesian authorities from going to Dili to bring his body back.

She was kept in Jakarta where a coffin arrived three days later. She was unable to identify the body because she was told Kamal had been buried immediately and then exhumed, rendering him unrecognisable.

Kamal's sister, Nadiah, says that when her uncle helped to bury the body in the grave in Bukit Kiara, Kuala Lumpur, he remarked that the body seemed too tall.

"Who knows, maybe it's a Timorese in Kamal's place," she speculates.

Her father, Ahmed Bamadhaj, however, believes it's his son's body, saying he had recognised Kamal's hair. The alternative, that it's not Kamal's body, is too terrible for him to contemplate.

Ahmed remembers a conversation he had with Kamal the last time he saw his son.

"He said to me: 'You know, Aba, there are some things in this world that are worth fighting for. And if it is going to cost me my life, I am prepared to give it.'

"I knew then that I could not stop him from doing what he believed in. I could only tell him to be careful."

But many, including East Timorese leader Jose Ramos Horta, who had used Kamal as a courier, and his mother, believe Kamal was marked for death by the army intelligence.

Says Todd, "He was deliberately targeted and murdered."

In Punitive Damage, Timorese activist Abel Guterras paid Kamal a moving tribute:

"He was a friend; a foreigner who came and showed his solidarity with us. It was sad that he came to our land and died for our freedom."

Published in The Star May 9, 2000

The Boy Who Loved People

by Ong Ju Lin

NINE years after Kamal Bamadhaj's death, as East Timor prepares for its independence from Indonesia, the young man is barely remembered by most Malaysians. But for his father, businessman Ahmed Bamadhaj, it is as if his son had died the day before.

"I still have nightmares occasionally about how he was killed. I still see him. I go around the streets of KL and sometimes see someone who looks like Kamal from the back ... and hope against hope that it is him,'' says Ahmed, his voice thick with emotion.

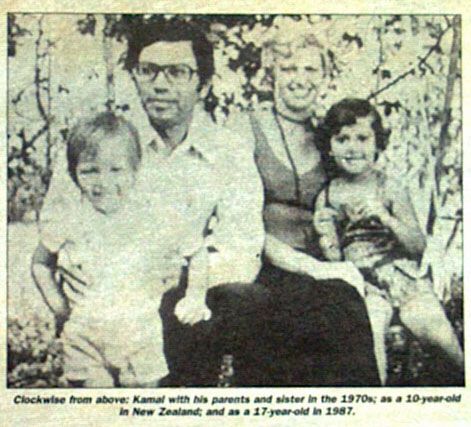

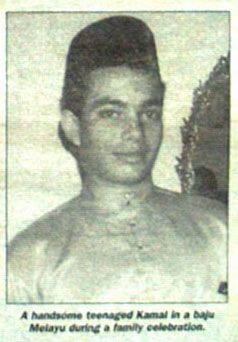

Kamal as born on Dec 23, 1970, the second child of Ahmed and his first wife, Helen Todd. They have two daughters, Nadiah, 31, and Haanim, 22.

Ahmed, who had never spoken openly about his son's death, remembers Kamal as an extraordinary child. As a young boy, he had shown a glimpse of the man he was to be.

"Kamal was a curious child and was always enthusiastic about learning new things. He was popular with everyone. He moved around without barriers or any hang-ups. And he was thoughtful and compassionate towards the less privileged,'' says his father at his home in Kuala Lumpur.

Ahmed recalls an incident during Hari Raya when Kamal was eight. "We had done our Hari Raya shopping and Kamal approached me and very gently asked, "Can you buy a pair of shoes for my friend?' I asked him why and he replied that his friend was poor and that he needed new shoes to replace his tattered ones. That was Kamal.

With his university friends, Kamal was known as the "peacemaker''.

"In debates, he was always calming everyone down, resolving conflicts and finding the middle way,'' says Elisabeth Wong who now works with the human rights organisation, Suaram.

Rather than being sucked into the arguments about capitalism or socialism as the end to poverty and social ills, Kamal believed that there were many other unexplored alternatives.

In a diary entry entitled, Dreams of a Thousand Roads, Kamal wrote: "While we were busy becoming more entrenched in the 'to be a socialist or to be a capitalist' debate, the fundamental aims of our loving humanitarian idealism (promoting social justice, creating egalitarianism, helping those with nothing no food, no shelter, no self-esteem) was fading away.''

Kamal's ideas on justice reflected his personality. He was described by his friends as someone who was liked by people because he was warm, personal and generous to everyone he met.

"Kamal was a compassionate young man. He had a big heart and a tremendous conviction toward humanitarianism,'' says Wong. The first time Wong met Kamal, he had bounded up to her to ask her if she was interested in joining a peace protest against Indonesia.

"He was barefoot. When I asked him why he went around kaki ayam, he replied that one must feel close to Mother Earth. He was also a devout vegetarian,'' Wong says.

Kamal's affinity to the plight of the East Timorese was no surprise to those who knew him. He grew up in a family where political awareness and social activism were discussed openly. Kamal's mother, Helen Todd, was a great influence.

A New Zealander, she married Ahmed Bamadhaj in 1968. In 1977 she gained her Malaysian citizenship and joined the New Straits Times as a journalist, writing under the byline Halinah Todd. She resigned from the paper in 1985.

Nadiah recalls that she and Kamal were exposed to many socio-political issues by their mother, including abuses by institutions of power. In Aksi Write (Rhino Press, 1997), a book by Nadiah on Kamal and his diaries, she wrote of Kamal's early influences.

Once such account was when Kamal was 11. Todd had taken him to Tasik Bera in Pahang to write on how the Felda land schemes were drying up the lake which the Semelai tribe depended on. Nadiah remembers Todd and Kamal staying up all night while the tribal elders nursed a sick child.

Todd was, and still is, involved in Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM), a project to eradicate poverty among the hard-core poor.

During his teens, Kamal worked in Sabak Bernam, Selangor, hauling bags of poultry feed for the farmers who were involved in the project. Later, using the same AIM concepts, he tried to implement the project in East Timor in 1990. Todd, who was divorced from Ahmed when Kamal was still a boy, will accomplish her son's dream by implementing a similar project in East Timor later this year.

Kamal first became interested in East Timor in 1989, as a result of his involvement in student activism at the University of New South Wales, Australia. He became part of the Network of Overseas Student Collectives (Nosca), a highly politicised student group consisting of mainly Malaysians, campaigning on domestic and international issues.

Despite giving so much of his time to his activism work, writing (he was extremely prolific, judging from his letters, diary entries and poems) and weekend jobs to support himself, Kamal was a brilliant and conscientious student, consistently scoring A's, says Ahmed.

In 1990, Kamal visited East Timor for the first time and witnessed for himself the situation which he had only read and heard about. This visit was crucial in making Kamal return to the troubled territory a year later.

Nadiah remembers that the last time she saw Kamal was a year before he was killed, just after his travels. "I remember that he was really troubled. He had just come back from East Timor and had witnessed the extent of the suffering there. He came back to Kuala Lumpur and was shocked that people were completely clueless about East Timor.''

A passage that Kamal wrote in a letter to his parents at the end of 1990 sheds some light on his concern and frustration:

"The Timorese are surrounded by fear. Fear like I've never felt before. There are intelligence and military people everywhere and hence it is difficult to get into conversation with people who are frightened or suspicious or both!

"I met victims of torture and people who had lost most of their families in the massacre of the 1970s when Indonesia invaded East Timor ... the most glaring thing was the huge military presence and the atmosphere of fear.

"People are still being taken away by the military at night and killed. (They) ... seem to have no one to appeal to ... no protection. It is frustrating and scary.''

From then on, all his activities were focused on his political beliefs aimed at social change. He took up the Asian studies programme, giving up law studies for he had begun to believe that little change could come out of the human rights situation in South-East Asia through legal channels.

With Tian Chua, Kamal founded Aksi, an off-shoot of Nosca, to raise awareness on human rights issues in Indonesia. Chua, a human rights activist and Keadilan vice-president, remembers Kamal as an enthusiastic, energetic young man whose passion for justice was infectious.

In commemorating the death of Kamal in a public forum welcoming East Timor leaders Xanana Gusmao and Jose Ramos Horta in February, Chua said: "There comes a time when one has to make a decision whether to stand on the sidelines or stand in solidarity with one's fellow man.''

Undoubtedly, Kamal chose the latter, and paid the price with his life.

Published in The Star Malaysia, (www.thestar.com.my) May 5, 2000

WHEN the Indonesian soldiers started pumping bullets into the East Timorese protesters at the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili on Nov 12, 1991, Malaysian activist Kamal Bamadhaj was near the front of the crowd.

He somehow survived the murderous hail, apparently sustaining only an arm injury, acording to a medical report his mother, Helen Todd received later. Eye-witnesses saw him walking away alone from the scene of carnage, barefoot.

In the documentary, Punitive Damage, Jose Verdial, a Timorese who took part in the demonstration, said he saw Kamal walking towards him, outside the cemetery, when a military truck that was following him pulled up next to him. An argument ensued, apparently over the camera Kamal was holding.

Seconds later, Kamal was shot in his chest by a military intelligence officer who had come out of the truck. He was left lying on the roadside. Kamal did not die immediately and had managed to flag down a passing Red Cross ambulance.

"When he was helped by the Red Cross, he was still talking,'' recounted Verdial. "Every time he spoke, blood gushed out from his wound.''

Further investigations by Todd revealed that Kamal died of blood loss as a result of delays in getting him to the hospital. The Red Cross ambulance was stopped twice by military and police road blocks.

At the second block, the police forced the ambulance driver into a police station compound and demanded he dump Kamal there. The courageous driver refused. He was finally allowed to send Kamal, who was bleeding profusely, to hospital. By that time, it was too late. He died 20 minutes later.

In Punitive Damage, American journalist Allan Nairn, who knew Kamal, recalled how tense and explosive the situation was in Dili, following the killing of a Timorese youth, Sebastiao Gomes, in a church by Indonesian soldiers on Oct 28 and the cancellation of the United Nations sponsored visit by a delegation of Portuguese parliamentarians on Nov 3.

Nairn said that when the soldiers attacked the Motael Church, it stunned the people because their "final sanctuary had been violated."

When word got out that the delegation's visit had been called off, the Timorese were in total despair. They had pinned tremendous hopes on the visit. At last, after 16 years of brutal oppression and isolation, the world would finally learn of their plight.

Many of the Timorese, defying the authorities' warnings of reprisal if they spoke to the Portuguese, had been preparing to gain the delegation's attention with banners and petitions. With the beacon of hope extinguished, they feared they would be singled out and killed.

Kamal, who knew many of the young Timorese, felt their fear and despair. He called his Australian girlfriend, Bibi Langker, in Sydney begging her to do something.

"He was desperate for the Portuguese to come. He asked me to go to the embassy to get them to come. He was really, really upset," she said in Punitive Damage.

When the Timorese decided to organise a memorial march for Gomes, Kamal begged the Western journalists (who were staying in the same hotel with him in Dili) to be present in the hope it would prevent violence by the Indonesian troops.

"Kamal himself was actually quite nervous about going. Then he decided to go and he got himself a camera," said Nairn.

Helen Todd marvels that "this boy who could never get up in the morning" set his alarm clock for 5.30am and woke everyone else.

The march started from the church near the beach and moved on to the cemetery. As they went along, the protestors pulled out banners calling for freedom.

As they gathered in the cemetery, Indonesian soldiers arrived and started shooting. "I couldn't believe it. At first I thought they were firing blanks. Then I saw people crumpling. They were being shot in the back as they tried to escape," recounted Nairn.

He said when the shooting stopped, the soldiers moved in and beat and stabbed the hapless Timorese still trapped in the cemetery.

Nairn, who sustained a cracked skull, said he survived because he shouted to the soldiers that he was American. He guessed, apparently correctly, that the Indonesians wouldn't kill a citizen of a nation which was supplying them with the guns and bullets.

A total of 271 people died that day, including Kamal, Malaysia's only casualty in the East Timorese cause.

Todd was prevented by the Indonesian authorities from going to Dili to bring his body back.

She was kept in Jakarta where a coffin arrived three days later. She was unable to identify the body because she was told Kamal had been buried immediately and then exhumed, rendering him unrecognisable.

Kamal's sister, Nadiah, says that when her uncle helped to bury the body in the grave in Bukit Kiara, Kuala Lumpur, he remarked that the body seemed too tall.

"Who knows, maybe it's a Timorese in Kamal's place," she speculates.

Her father, Ahmed Bamadhaj, however, believes it's his son's body, saying he had recognised Kamal's hair. The alternative, that it's not Kamal's body, is too terrible for him to contemplate.

Ahmed remembers a conversation he had with Kamal the last time he saw his son.

"He said to me: 'You know, Aba, there are some things in this world that are worth fighting for. And if it is going to cost me my life, I am prepared to give it.'

"I knew then that I could not stop him from doing what he believed in. I could only tell him to be careful."

But many, including East Timorese leader Jose Ramos Horta, who had used Kamal as a courier, and his mother, believe Kamal was marked for death by the army intelligence.

Says Todd, "He was deliberately targeted and murdered."

In Punitive Damage, Timorese activist Abel Guterras paid Kamal a moving tribute:

"He was a friend; a foreigner who came and showed his solidarity with us. It was sad that he came to our land and died for our freedom."

Published in The Star May 9, 2000

The Boy Who Loved People

by Ong Ju Lin

NINE years after Kamal Bamadhaj's death, as East Timor prepares for its independence from Indonesia, the young man is barely remembered by most Malaysians. But for his father, businessman Ahmed Bamadhaj, it is as if his son had died the day before.

"I still have nightmares occasionally about how he was killed. I still see him. I go around the streets of KL and sometimes see someone who looks like Kamal from the back ... and hope against hope that it is him,'' says Ahmed, his voice thick with emotion.

Kamal as born on Dec 23, 1970, the second child of Ahmed and his first wife, Helen Todd. They have two daughters, Nadiah, 31, and Haanim, 22.

Ahmed, who had never spoken openly about his son's death, remembers Kamal as an extraordinary child. As a young boy, he had shown a glimpse of the man he was to be.

"Kamal was a curious child and was always enthusiastic about learning new things. He was popular with everyone. He moved around without barriers or any hang-ups. And he was thoughtful and compassionate towards the less privileged,'' says his father at his home in Kuala Lumpur.

Ahmed recalls an incident during Hari Raya when Kamal was eight. "We had done our Hari Raya shopping and Kamal approached me and very gently asked, "Can you buy a pair of shoes for my friend?' I asked him why and he replied that his friend was poor and that he needed new shoes to replace his tattered ones. That was Kamal.

With his university friends, Kamal was known as the "peacemaker''.

"In debates, he was always calming everyone down, resolving conflicts and finding the middle way,'' says Elisabeth Wong who now works with the human rights organisation, Suaram.

Rather than being sucked into the arguments about capitalism or socialism as the end to poverty and social ills, Kamal believed that there were many other unexplored alternatives.

In a diary entry entitled, Dreams of a Thousand Roads, Kamal wrote: "While we were busy becoming more entrenched in the 'to be a socialist or to be a capitalist' debate, the fundamental aims of our loving humanitarian idealism (promoting social justice, creating egalitarianism, helping those with nothing no food, no shelter, no self-esteem) was fading away.''

Kamal's ideas on justice reflected his personality. He was described by his friends as someone who was liked by people because he was warm, personal and generous to everyone he met.

"Kamal was a compassionate young man. He had a big heart and a tremendous conviction toward humanitarianism,'' says Wong. The first time Wong met Kamal, he had bounded up to her to ask her if she was interested in joining a peace protest against Indonesia.

"He was barefoot. When I asked him why he went around kaki ayam, he replied that one must feel close to Mother Earth. He was also a devout vegetarian,'' Wong says.

Kamal's affinity to the plight of the East Timorese was no surprise to those who knew him. He grew up in a family where political awareness and social activism were discussed openly. Kamal's mother, Helen Todd, was a great influence.

A New Zealander, she married Ahmed Bamadhaj in 1968. In 1977 she gained her Malaysian citizenship and joined the New Straits Times as a journalist, writing under the byline Halinah Todd. She resigned from the paper in 1985.

Nadiah recalls that she and Kamal were exposed to many socio-political issues by their mother, including abuses by institutions of power. In Aksi Write (Rhino Press, 1997), a book by Nadiah on Kamal and his diaries, she wrote of Kamal's early influences.

Once such account was when Kamal was 11. Todd had taken him to Tasik Bera in Pahang to write on how the Felda land schemes were drying up the lake which the Semelai tribe depended on. Nadiah remembers Todd and Kamal staying up all night while the tribal elders nursed a sick child.

Todd was, and still is, involved in Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM), a project to eradicate poverty among the hard-core poor.

During his teens, Kamal worked in Sabak Bernam, Selangor, hauling bags of poultry feed for the farmers who were involved in the project. Later, using the same AIM concepts, he tried to implement the project in East Timor in 1990. Todd, who was divorced from Ahmed when Kamal was still a boy, will accomplish her son's dream by implementing a similar project in East Timor later this year.

Kamal first became interested in East Timor in 1989, as a result of his involvement in student activism at the University of New South Wales, Australia. He became part of the Network of Overseas Student Collectives (Nosca), a highly politicised student group consisting of mainly Malaysians, campaigning on domestic and international issues.

Despite giving so much of his time to his activism work, writing (he was extremely prolific, judging from his letters, diary entries and poems) and weekend jobs to support himself, Kamal was a brilliant and conscientious student, consistently scoring A's, says Ahmed.

In 1990, Kamal visited East Timor for the first time and witnessed for himself the situation which he had only read and heard about. This visit was crucial in making Kamal return to the troubled territory a year later.

Nadiah remembers that the last time she saw Kamal was a year before he was killed, just after his travels. "I remember that he was really troubled. He had just come back from East Timor and had witnessed the extent of the suffering there. He came back to Kuala Lumpur and was shocked that people were completely clueless about East Timor.''

A passage that Kamal wrote in a letter to his parents at the end of 1990 sheds some light on his concern and frustration:

"The Timorese are surrounded by fear. Fear like I've never felt before. There are intelligence and military people everywhere and hence it is difficult to get into conversation with people who are frightened or suspicious or both!

"I met victims of torture and people who had lost most of their families in the massacre of the 1970s when Indonesia invaded East Timor ... the most glaring thing was the huge military presence and the atmosphere of fear.

"People are still being taken away by the military at night and killed. (They) ... seem to have no one to appeal to ... no protection. It is frustrating and scary.''

From then on, all his activities were focused on his political beliefs aimed at social change. He took up the Asian studies programme, giving up law studies for he had begun to believe that little change could come out of the human rights situation in South-East Asia through legal channels.

With Tian Chua, Kamal founded Aksi, an off-shoot of Nosca, to raise awareness on human rights issues in Indonesia. Chua, a human rights activist and Keadilan vice-president, remembers Kamal as an enthusiastic, energetic young man whose passion for justice was infectious.

In commemorating the death of Kamal in a public forum welcoming East Timor leaders Xanana Gusmao and Jose Ramos Horta in February, Chua said: "There comes a time when one has to make a decision whether to stand on the sidelines or stand in solidarity with one's fellow man.''

Undoubtedly, Kamal chose the latter, and paid the price with his life.

Published in The Star Malaysia, (www.thestar.com.my) May 5, 2000

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)